“If it can be written or thought, it can be filmed.”

Stanley Kubrick

While Stanley Kubrick’s words could be an observation on the intrinsic flexibility of film (or a somewhat arrogant assessment of his own skill as a director), it is more fundamentally a comment on the flow of ideas across mediums. This edition explores this process of adaptation as ideas move from one medium to another, how a play can become a film and then a stage musical (as with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and West Side Story). Many factors drive the adaptation of ideas into different mediums: a writer or director’s interest in a new interpretation, new technologies and materials, as well as commercial opportunities. This edition of the archive examines why some adaptations can be straightforward, while others are more difficult. It highlights that adaptation is often a source of inspiration in the emergence of new art forms and representations. It also explores how certain forms of representation become established across mediums. Over time, multiple acts of adaptation force both the artist and the viewer to reexamine the work and how it relates to the moment of its creation, reemphasising the importance of understanding the specific meaning of ideas and the qualities of mediums when moving an idea from medium to medium.

Kubrick’s belief that any ‘written or thought’ can be expressed on film stems from the medium’s ability to combine a number of different kinds of information. Film contains acting, dialogue, music, choreography, visual composition, and symbolism. These elements, combined dynamically together through sequences of moving images and editing, create a vast and varied dense medium, capable of profound realism and intense abstraction. However, Kubrick makes an error in his understanding of the adaptation process. By positioning film as the inevitable endpoint of expression and suggesting it is an all-encompassing medium, capable of capturing any idea, he suggests a hierarchy amongst mediums, and fails to recognise that the key aspect of adapting ideas into new mediums is suitability. It is not a question of whether film can capture any ‘thought or written’ idea, rather he should ask: is film the correct medium to effectively convey this particular idea? Only by understanding the relationship between the idea’s desired message and the qualities of a medium can we see how an idea could be adapted, and which mediums can carry the idea.

There are three situations where medium to medium adaptation has a high probability of being successful, of being ‘suitable’. When the original and adapted medium have a high degree of ‘flexibility’, when the two mediums are very ‘close’ in form or when the ideas operate at similar levels of abstraction. Flexibility relates to the medium’s inherent ability to capture or convey ideas in many different ways. Theatre is an example; plays are literally designed to be reinterpreted, as each new performance is its own new ‘thing’; they want to be adapted. As a result, it is easy to move an idea from theatre into another medium like film. A film’s density as a medium is an advantage, as its breadth leaves space for the director to mould ideas in new and interesting ways. The suitability of stage-to-screen adaptations is evident from their success at the Oscars: ‘Amadeus’, ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ and ‘12 Angry Men’, all either were nominated or won the Oscar for Best Picture.

Inherent similarity between the two mediums also helps ensure suitability for adaptation, as with poetry into dance. T.S. Eliot’s ‘Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats’ poem was adapted into the hugely successful musical, ‘Cats’. which ran for 21 years in the West End. Both poetry and dance deal with ideas of rhythm, meter and repetition, and use symbolism and figurative, abstracted language (whether literal language or the language of the body) to create meaning and emotion. Both mediums have a similar relationship to abstraction, and therefore, ideas can move back and forth with relative ease. This is also the case in the relationship between the mediums of abstract art and music, explored by Kandinsky. He recognised the connection between abstract ideas conveyed through music and the new forms of visual representation developing in the years between 1910-1930 and believed that adapting musical forms into paintings could generate a spiritual reaction in the viewer. As he said, ‘the artist is the hand that purposely sets the soul vibrating by means of this or that key. Thus it is clear that the harmony of colours can only be based upon the principle of purposefully touching the human soul’. He draws here the connection between music ‘this or that key’, painting, ‘the harmony of colours’ and a spiritual revelation, ‘touching the human soul’. Theatre and television is a further example where the similarity of the mediums affects their suitability for adaptation. Bignell argues that both theatre and the TV studios have connotations of privacy, family, and the reproduction of social relations, and that television drama is ‘the drama of the small enclosed room, in which a few characters lived out their private experience of an unseen public world’. In both mediums, ‘speech, not action, is a key component of this ensemble of creative means’.

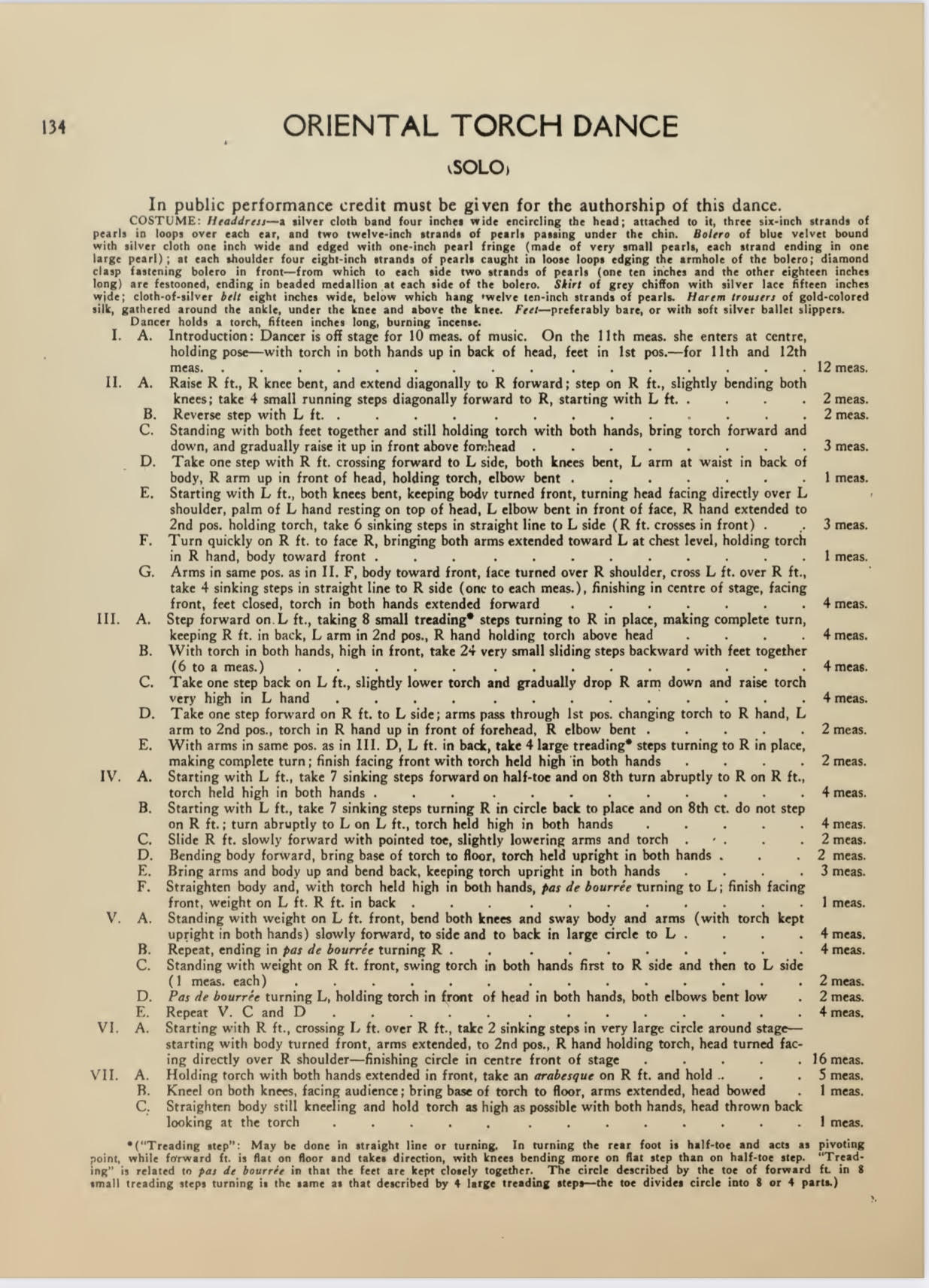

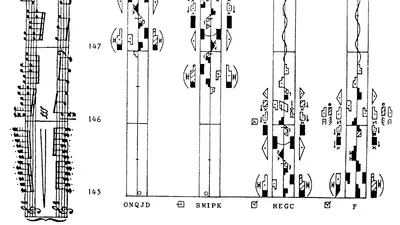

By contrast, when a medium is either inflexible or dissimilar to other medium in the adaptation process, then issues emerge, as is evident with ballet and opera. Ballet is difficult to adapt to other mediums because of its specific physical and aesthetic requirements, and in particular, the complex spatial and temporal relationship between dancers, defined specifically to be exacting and rigid through choreographed practice. This creates an impressive consistency in ballet, a feature that is often emphasised in the works themselves through complex moves performed by an entire chorus of dancers at once, where any slight deviation from perfection is immediately visible to the audience. This rigour and rigidity of ballet can be seen in the notation of the important Russian ballet choreographer, Alexis Kosloff. Further, a page from Rudolf Laban’s Schrifttanz (1928), the origin of labanotation, also shows the extent to which dance can be rigorously codified, leaving potentially little room for interpretation. Opera is a similarly difficult medium to translate. Kenneth Clark argued that opera is an illogical art form which can communicate complex emotions and situations which are ‘too revealing to be said or too mysterious’. These capabilities of the medium, handling ideas that cannot be articulated by speech or other forms of visual representation, make opera uniquely valuable, but make adapting it very challenging. So much so that when the British Film Institute drew up a list of the best top ten opera films ever made, it could only identify nine!

The process of moving between mediums presents opportunities and challenges and can act as a stimulus to creativity, especially when this involves new technologies and techniques. The painters Monet and Hockney were both focused on capturing the beauty and complexity of the natural world. New developments in tubes of slow-drying paint enabled Monet to paint in ‘en plein air’, which enhanced his ability to record the changing details of weather and light, particularly in his 250 paintings of his ponds and gardens in Giverny. Hockney has also exploited the capability of newly emerging technology to capture the changing natural world. In his work The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, made with an iPad, he recorded the individual steps of his ‘painting process’, step by step, which, when played back, enables the viewer to see the effects of rain falling on a pond and the creation of ripples on the water’s surface. In both cases, the artists leveraged the new mediums to find better ways to communicate the changing and complex natural world.

The process of adaptation to new mediums, and in particular with film at the turn of the 20th century, creates a feedback effect. As Robert Hughes notes, the dynamic nature of film was critical to the development of painting and Cubism, inspiring Picasso and Braque to break from single-point perspective to present an object simultaneously from multiple viewpoints, similarly to how a film can capture multiple angles of an object. This intensity of experimentation continues to this day as artists and designers attempt to understand what kind of ideas and stories work best in a particular medium, developing new forms and discarding elements as they become less interesting. This is evident in the rapid development of video games. Elements that were once characteristic of early arcade games, like three lives or endless waves of enemies, were replaced with games that emphasised continuous learning as home consoles became the dominant video game platform. This also applies to works that have undergone several adaptations over time. This can be seen in the evolution of the character, Dracula. According to Bignell, the BBC TV 1977 adaptation Count Dracula drew on the aristocratic iconography of Bela Lugosi in Browning’s 1931 film, which in turn rested on two theatrical adaptations by Deane and Balderston in the 1920s. These theatrical representations established the imagery of evening dress and opera cloak; theatrical symbols which carried over into film, creating the character’s resemblance to the sinister hypnotists, seducers, and evil aristocrats of Victorian melodramatic theatre.

Examining medium-to-medium adaptation reemphasises the importance of understanding the specific context when determining both the nature of creativity and the interrelationship between idea, medium and suitability. It also suggests, adaptation is easier with flexible mediums, adaptation is more straightforward between similar mediums or when both mediums operate at a similar level of abstraction. The corollary occurs when mediums are inflexible or mediums are very different, leading to problems of adaptation. However, these differences in medium are also valuable; they can preserve unique interpretations and can help spark new levels of creativity as ideas flow between mediums, keeping ideas in motion and therefore fresh and interesting. The analysis also suggests that while Marshall McLuhan’s insights on the influence of the medium on the message remain valuable, understanding the degree of harmony between the idea and the medium is also critical.

Leave a comment